Kishore Desai – A Maestro Who Strummed Million Hearts

- Shankar Iyer | burmanfan@gmail.com

Listening to the RD Burman’s iconic ‘Tum Bin Jaan Kahaan’ (Pyar Ka Mausam) without Kishore Desai’s mandolin strings is much similar to being served Mumbai’s famed vada pav without vada and the dry garlic chutney! The ultimate freedom song ‘Aaj Phir Jeene Ki Tamanna hai’ (Guide) or Ai Meri Zohra zabeen (Waqt) without mandolin would also be like the Pizza being served as just without Cheez!

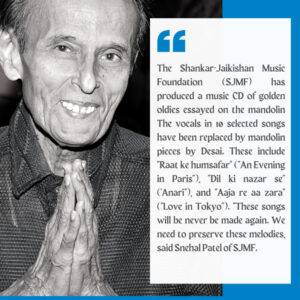

Music lovers have binged on these and many such classics, not knowing about the man who added the spice of mandolin strings! Meet Kishore Desai, who, at the age of 84, displays the same energy and enthusiasm when asked to strum mandolin pieces of this yesteryear’s melodies.

Kishore Desai has immortalized hundreds of songs but remained unsung like many of his fellow musicians who silently ornamented the tunes composed decades ago but are listeners who rejoice even today. He is a galaxy scattered somewhere in the infinite universe. But one doesn’t need a telescope to locate him. Just walk into his house in Borivilli (a Mumbai suburb) and he will receive one and all warmly.

Though the mandolin’s use has been given a burial by electronic instruments, it’s important to know its contribution to enhancing the melody of retro songs that are hummed over generations. It’s like the instrument obeying its master and reflecting the slightest nuances with the inputs of the player. With a soft touch and strumming one can hear an alive, deep, crisp ring, producing freedom of a tone.

Though the mandolin’s use has been given a burial by electronic instruments, it’s important to know its contribution to enhancing the melody of retro songs that are hummed over generations. It’s like the instrument obeying its master and reflecting the slightest nuances with the inputs of the player. With a soft touch and strumming one can hear an alive, deep, crisp ring, producing freedom of a tone.

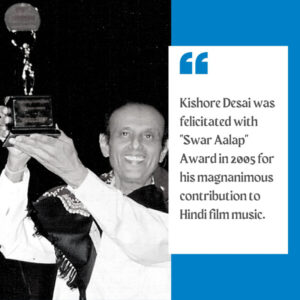

A child prodigy whose talent was identified by none other than legendary Kalyanji Shah of the Kalyanji Anandi duo, Kishorebhai is equally adept at playing the harmonium and rendering some of the best classical songs. It was in 2005 that his contribution to Hindi film music was recognized when he has bestowed the prestigious Dadasaheb Phalke Lifetime Achievement Award.

A face behind the curtains and behind the mandolin whose journey deserves to be told. Born in a traditional Gujarati family of industrialists having roots in Umrala village of Gujarat’s Bhavnagar district and later based in Mumbai, Kishorebhai decided to embark on a different adventure- a career in music. A choice he could firmly stand on after the support and direction given by his father and grandfather, and the teachings of Ustaads, which soon landed him to play his first song at the age of 15 for a film! Often complimented for his extraordinary talent and understanding of music, he was also known as the fastest notation writer in the Indian style.

Can you share with us about your musical training and how did it begin?

I went to Professor Deodhar’s school of Indian Music. I completed the Raag Bodh syllabus and learned the fundamentals of playing the Harmonium and mandolin from Shastriji. This was at the instance of Ishwar Kaka and thereafter at 14 years, my father’s close friend Jayanand Khira got me to become a Gunda-bundh shagird of the illustrious vocalist Ustad Khadim Hussain Khan of the Agra Gharana (school of music). Starting with Raag Yaman Kalyan, Ustadji taught me very intensively about raagdari and classical music.

After a very fruitful tutelage, I revealed to him that I wanted to learn the sarod to which he said that I go ahead and come back to him for instilling the ‘vocal’ element into the instrument! My father took me to the revered Ustad Ali Akbar Khan of Maihar Gharana who took a special interest in tutoring me. He literally placed my fingers on the instrument, introducing me to each note. I still practice the paltaas taught by him. But, being an extremely busy artist with national and international engagements, he could not continue with me for long. So, I started learning from the Late Ustad Bahadur Khan.

My father was keenly interested in classical music. His influential friends like Jayanand Khira, Babubhai Raja, and Dr. Vora supported Brij Narayanji to start the musical foundation ‘Sur Singaar Sansad’ to promote Hindustani classical music. I was truly blessed to be in an inspiring musical atmosphere. I also became Mr. Ramchandra Lalbhai Banker’s (Babubhai of Lal Mills fame) only disciple ever. This friend of my father’s was amazing with his heightened sense of rhythm and its applications. He was a master of unknown taals (beats) and excelled in rhythm structures with half and one-quarter beats (maatra).

You were already in a highly charged classical musical environment, then what took you to films?

My conservative but art-promoting school ‘New Era’, encouraged me to play music, but non-film. The legendary Anil Biswas heard me play mandolin in a competition organized by Bharatiya Sangeet Kalakar Mandal where he was one of the judges. He was so impressed with me that he got a special cup made for me as the other judges had not awarded me the first prize. He told me that I had played uniquely and that according to him I was the recipient of something more than the first place. My other similar victories were at the competitions held by Sur Singaar Sansad, Amruta, Pandit Adityaram Sangeet Institute, etc. I performed at the prestigious Swami Haridas Sangeet Sammelan in 1956.

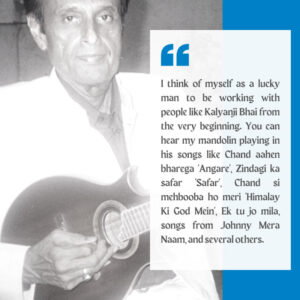

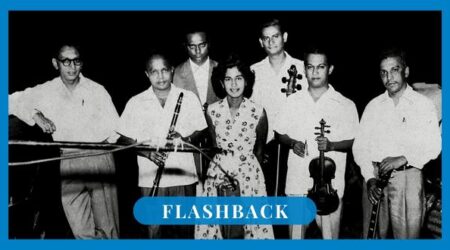

I had started playing the mandolin for my close friend Kalyanjibhai’s orchestra shows and was thoroughly enjoying it. My performance of Awaara Hoon on mandolin got me the Gene Kelly Film Festival Award and Shankarji (Shankar-Jaikishan) invited me to play as a musician in their recordings. Kalyanjibhai who used to regularly work with him (played clarinet for Tune haay mere zakhm-e- jigar ko’ in Nagina, etc.) was largely responsible for all this good happening to me. It was then and there that Shankarji introduced me to Raj Kapoor, Jaykumar Parte, Dattaramji, Narvekar, etc. I knew Dattaram who re-endorsed my credentials to Shankarji. Later, I played for two songs in Shankar-Jaikishan’s film Basant Bahar.

I had started playing the mandolin for my close friend Kalyanjibhai’s orchestra shows and was thoroughly enjoying it. My performance of Awaara Hoon on mandolin got me the Gene Kelly Film Festival Award and Shankarji (Shankar-Jaikishan) invited me to play as a musician in their recordings. Kalyanjibhai who used to regularly work with him (played clarinet for Tune haay mere zakhm-e- jigar ko’ in Nagina, etc.) was largely responsible for all this good happening to me. It was then and there that Shankarji introduced me to Raj Kapoor, Jaykumar Parte, Dattaramji, Narvekar, etc. I knew Dattaram who re-endorsed my credentials to Shankarji. Later, I played for two songs in Shankar-Jaikishan’s film Basant Bahar.

Basant Bahar was released in 1955. Wasn’t your earliest film song recording in 1952 for a song by SD Batish?

In 1952, I played mandolin for one song for the film Bahu Beti under the music direction of SD Batish which was a Geeta Roy number Dhumak dhumak mora baje ghungharva and for the film’s background music. As I was a kid and short-statured, I was made to sit on a high chair and play mandolin to reach the microphone placed at the height of four and a half feet at Bombay Lab. George Pacheco was the arranger and Shareef Bhai, was the dholak player.

But prior to that I assisted and played for music director Pandit Shivram Krishna in Subah Ki Manzil, a film starring Nimmi and Shekhar which got shelved. I distinctly remember the songs Main Apna Deepak tufaanon mein by Rafi Sahab and another 2/4 rhythm-based fast-duet song of his which was picturized well. So, technically my first film songs are these followed by Dhumak dhumak.

‘Basant Bahar’ was the first film whose songs I had played for Shankar-Jaikishan. Before that, I had played the mandolin along with my mentor David Saab for Anil Biswas’ Heer. The Hemant Kumar solo, Preet karoge bin dekhe fetched me a princely payment of Rs.100/- in 1954. That was solely because I was a ‘classical musician’ invited by Anilda himself but soon I was clamoring to do just that. Pt. Shivram Krishna, Sardar Malik (Maa Ke Aansoo onwards about 15 films), C Ramachandra (Bahurani onwards about 18 films), and Roshan (Soorat Aur Seerat onwards about 12 films) were some of the renowned directors whom I have assisted.

Did you take any further lessons considering that you were from purely classical training?

Yes, indeed, and from none other than the great mandolin player Isaac David (David Saab). During a recording together, he commented that he liked my playing but that I would not fit in the industry. He asked me why my stroking was from down to up which is unnatural and against gravity. When he learned that it was Ustad Bahadur Khan’s rigorous training that had resulted in such powerful stroking, he complimented me but cautioned that the tonal quality changed drastically due to this method of playing mandolin. Upon my request, he accepted to teach me, but as an exceptional case as he never taught.

Tell us about your association and bond with C. Ramchandra.

C Ramchandra treated me like his son. Besides my long association with him as his assistant in the sixties and early seventies, I played a lot for him. Tu chhupi hai kahaan had long sarod pieces by me for Navrang.

Talking of Mukeshji instantly brings your exclusive songs to my mind Baharon se keh do, Tere labon ke mukabil, Mil na saka dil ko, and Mujhse Yun Rooth Kar. Why didn’t you get the career boost and big fame you deserved for these excellent compositions?

These were non-film songs recorded by Mukeshji for HMV in the mid-sixties. All songs got popular and I can say that I suddenly noticed. Rajkumar Barjatya of Rajshri Pictures was so smitten by Mil na saka dil ko that he decided to make a movie around it and with difficulty he bought over that private song from HMV. But he did not pursue the project much and dropped it later. I guess everybody gets their due and that I got what was written for me.

These were non-film songs recorded by Mukeshji for HMV in the mid-sixties. All songs got popular and I can say that I suddenly noticed. Rajkumar Barjatya of Rajshri Pictures was so smitten by Mil na saka dil ko that he decided to make a movie around it and with difficulty he bought over that private song from HMV. But he did not pursue the project much and dropped it later. I guess everybody gets their due and that I got what was written for me.

You arranged and played in Pandit Shivkumar Sharma’s albums, ‘Water’ and ‘Mountains’ by Music Today.

Pt. Shivkumar Sharma is not only my colleague but a dear old friend of mine. It is a pleasure to work on his projects. I also did the musical arrangements for his son, Rahul Sharma’s album ‘Confluence’ with pianist Richard Clayderman.

You are known as the fastest notation writer in the Indian style. How did that happen?

I was called to play sarod for Roshan Sahab’s ‘Chitralekha’ for the song Sakhi RI Mera man uljhe. This was the first time I played for him. What impressed him about me is that whatever phrases he expressed; I would play exactly those the next day. I would write them down quickly and precisely and practice them hard before playing them. As you know, he was Ustad Allaudeen Khan’s disciple, from Lahore. He was an excellent sarangi player and used the sarod beautifully in his songs. Master Sonikji and Omiji (Sonik-Omi duo), both independently always complimented me on my writing of notations.

What other instruments do you play besides the mandolin, Sarod, and Harmonium?

I have played Arabian instruments Aoud and Kanoon. Laxmikant Pyarelal has used these in their songs. I have played Banjo, Harp, Banjolin, Greek Bazouki, Mandola and Chong. In C Ramchandra’s Gharkul (Marathi), I played harp for Malmali taarunya maajhe.

You were close to Pancham and worked a lot for him. Tell me what was he like?

About RD? An absolute revolutionary! He was a creator. His classical approach was so good and similar in style to that of Ustad Ali Akbar Khan. Anna would say he has brought about good changes. Never before had anyone composed such a long mukhda as the one of Yeh jo muhabbat hai (Kati Patang).

Similarly, the lingering effects of Sandese Aate Hain depend on Desai’s art. Noor Mohd Qureshi, who played mandolin along with Desai remembers how they played together in DDLJ. We played the main song such as Tujhe Dekha To Yeh Jaana and Mehandi Laga Ke Rakhna. Qureshi said “It was always good to work with Kishorbhai. He really has very good hands He is a nice person who always remains cheerful.”

Comment (1)

The opening notes of tum bin japon jahan pemain my constant favourite along with Kishore Kumar’s majestic hum . Love spilleth over . Respect for Kishore Desai sir for being the aandolon magician . Kudos to swaralap for kindly bingung into focus these humble creators who have enlarged the expand of Indian music .