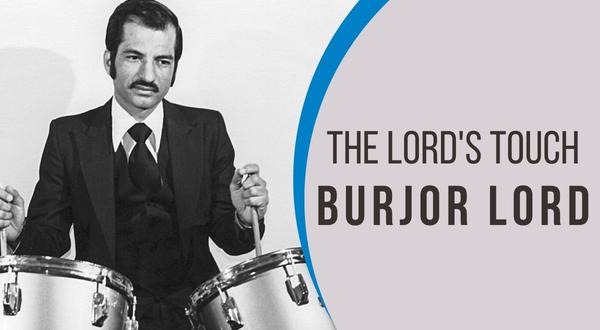

The Lord’s Touch – Burjor Lord

- Anisha Nandan | anisha.45687@gmail.com

- An extract from “The Unsung Heroes”, was published by Swar Aalap in 2010.

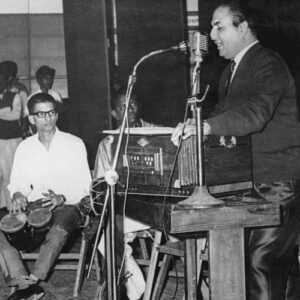

Burjor Lord, aka “Buji” Lord, is a beloved name in the music fraternity across India and around the globe. He hails from a widely established family in the music industry. When you hear songs like Chand Mera Dil, Sayonara, Aa Jaane Jaan, Mehbooba Mehbooba, etc., he has recorded 12,000+ songs to his credit. Only a true music enthusiast can appreciate how the xylophone and drums performed to give them more life and bring them together, it is a work of art.

The peak of his career drew massive attention from his fans, forming fan clubs, foreign tours, busy schedules, and recognition from esteemed personalities. He has not only given us songs but also memories, which may have touched each one of us in ways we know best. His work resonated with the pulse of the audience; it still does. When you see him play, the lord’s touch appears to be quite effortless. He is aware of what he is doing and follows the action with ease. In his own words, “I was non-filmi by nature.” He purposefully avoided the glitz and the film environment. He aspired to a life outside of films and work, and he has no regrets about that.

As firm and vibrant as the grasp on the drumsticks is Buji Lord’s sense of humor and wit. The list of instruments played for songs is as long as your arm. He won’t blow his horn even after receiving praise as a “world-class” musician; that’s just the way he is. He is shy and reserved when asked about his accomplishments, his innocent, almost childlike struggle to find words is admirable and amusing. But he’s chilled out and a great person to interact with. While legitimate efforts have been made to extract a decent career sketch of a highly sought-after instrumentalist of the Indian music industry, omissions may please be pardoned.

Read more about his life, as he speaks with sheer honesty. Get it straight from the horse’s mouth in this conversation.

Coming from a superbly talented family, was music an obvious choice for a career?

I was very keen on the merchant navy as I wanted to travel the world, but my matriculation results did not permit me to pursue my dreams. Also, wearing spectacles prevented that. Hence, I turned to music as a profession.

I see. So, what kind of musical training did you have?

I learned to play the Mouth Organ, piano accordion, and other instruments a bit since I was 7. To understand the Indian side, I even learned harmonium from Babu Singh and Tabla. I began practicing at six a.m. and continued until seven p.m.

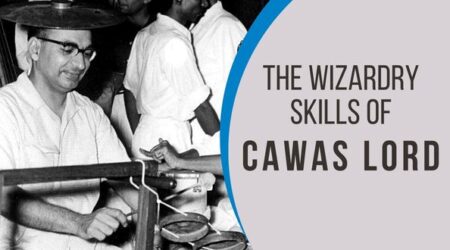

My father, Cawas Lord, was a strict taskmaster. He used to come up behind me and grab the drumsticks from my grip as I was practicing. If they slipped from my grip, I’d get struck with them on the knuckles, which hurt. But that’s all to perfect my grip, so it doesn’t fall when you’re playing fast. He was the nicest person to be around.

How would you describe your style of Drum playing?

The singer is most prominent in the Indian song, I would try not to disturb the song. I would add a few fancy touches where there were gaps. However, because there were too many instruments and they would all be playing the same pattern, there was less scope for innovation. Hi-hats and the banging of uppers caused by releasing the pedal together created an extremely unusual sequence that drew the attention of arranger Basuda.

Drummers all over the world have this big ‘hip’ image with a huge fan following like in the movies such as Teesri Manzil, so I’m sure it must be that.

Let me share an interesting fact with you. When my in-laws asked about their prospective son-in-law who worked in films, Ashaji told them that, contrary to their expectations, I was a total “non-filmi” by nature. Her positive comments about me put my hesitant in-laws at ease, and they decided to marry their daughter to me.

I believe that the first full-fledged film score you played was for music director Iqbal Quereshi’s Love in Simla ’60. Who were the others you worked with?

I played on all recordings for Usha Khanna, O P Nayyar, Roshan, Madan Mohan, Naushad, Khayyam, S D Burman, Jaidev, Ravi, Kalyanji-Anandji, Sapan-Jagmohan, Avinash Vyas, Salil Chowdhury, and Sardar Malik. Otherwise, from Husnlal-Bhagatram to Anu Malik to everyone, intermittently.

Speaking OP Nayyar Sahab, that you learned many things from him, can you give us more information on that?

Certainly. It was he, who told me to give the strokes of the Vibraphone when singers take a breath or when there were pauses. This was in contrast to the regular technique of giving strokes to the beat of any song. (Demonstrates this, singing Jaaiye aap kahaan jaayenge…). He was very precise and knew exactly what he wanted.

There was no bargaining about his requirements. Even if you were dissatisfied, you couldn’t ask for another “take.” Forget musicians; singers couldn’t do it. Almost military-like. Extremely punctual. Some world-class singers and musicians were sent back because they were late for his recordings. Overall, it was a pleasure to play for him. Our family was delighted when we worked with him because, unlike others, he used to start at nine and finish by eleven a.m. This allowed us to either leave earlier or work extra shifts on the same day!

What about the other mallet instrument you played – Glockenspiel, isn’t it a folk instrument?

Glock is a German instrument that is predominantly used in Western classical music. Kersi Lord introduced it to India for the first time in the fifties. Both of us played it for many songs as an accompaniment to the Sitar, Sarod, etc. In some songs, you can even hear combinations with Xylophone, Jal Tarang, Santoor, etc.

The bars are thinner and smaller than on other Mallet instruments, and there are no resonance pipes or motors. It was played as a solo instrument in lullabies (Nanhi kali sone chali) or plucking instruments such as Sitar, Mandolins, and others in Indian songs.

From the sixties, indisputably Vibraphone played by you is the highlight of countless songs like Chhupa lo yun dil mein pyar mera, Koi humdum na raha, Kuchh dil ne kaha, what is a Vibraphone?

It’s a mallet instrument having thin bars on one side and thick bars on the other. There are resonance pipes below and a motor for variable speed gives the back vibrations. There are soft and hard mallets used depending on the type and mood of the song. It adds a very definitive but subtle flavor to a song.

Considering you played Vibraphone, Xylophone, Glockenspiel, and other Mallet instruments, Percussions, and all western rhythm instruments for thirty energetic years from 1959, I would estimate that there are at least twelve thousand recorded tracks by you.

As far as I was concerned, no one in Nargol (Gujarat, where Buji stays) knew about my past life as a musician till you people (Swar Aalap) came back with the 2007 calendar and dug out dead musicians like me from the grave!

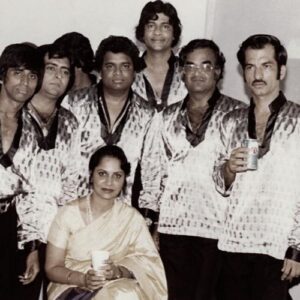

You also played a lot for live concerts around the world featuring big stars. Kersi and you have played and together have been hailed by expert American musicians as being amongst the world’s most remarkable musicians. Pandit Ravi Shankar chose you to play his detailed work for his stage shows. You even played in the historical rendition of “Ai mere Watan ke logon” when Prime Minister Nehru wept.

Pandit Nehru heard the sher of the song and broke into tears. In 1962, I played Timpani at the beginning of the song and Glock or Vibraphone for the recording and the live performance of the now historical song in Delhi. At one show at the Nathu La border at 15000 feet, where we had gone with C Ramchandra to entertain the Indian troops, the Chinese troops were watching us from 200 meters across the border with binoculars!

Why did daddy (Cawas Lord) insist on being ambidextrous?

A drummer needs to use both pairs of hands and feet, so daddy insisted that we use them all with equal ease. He used to insist on us doing exercises like tying shoelaces, buttoning shirts, opening & closing doors, keys, etc. with the left hand to increase its efficiency.

How was your entry into films? Did Cawas kaka take you around, introduce you to everybody, saying ‘yeh Mera beta hai’?

No, no. I appreciate that he didn’t do that. It was like this that brother Kersi fell sick. Or was it surgery? I can’t remember exactly, but since he was not playing that day for Shankar-Jaikishan’s recording, Dattaram, their rhythm arranger, who was just like a neighbor, proposed that I fill in for the recording.

Oh, would you give Dattaramji the credits for your first-ever break?

Yes, but it would not have happened without Kersi’s contribution. Had he been available, I wouldn’t have been called. Similarly, Kersi had gotten his first chance when Daddy had taken ill. I guess it runs in the family. But please do not misunderstand that the Lord’s family was waiting for each other to fall sick to progress!

We hear from your Guru-Bhai, Percussionist Homi Mullan, that you created some pieces on the drums which were extensively used in the industry.

This combination of the hi-hats and the banging of uppers by releasing the pedal created a very unusual sequence that caught arranger Basuda’s ears. It got widely used as a suspenseful music piece thereafter.

Which co-musician’s work did you like or admire?

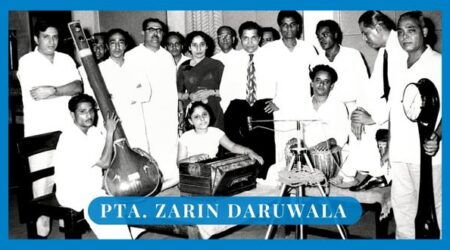

Daddy, Kersi, Manohari Singh, Uttam Singh, Oscar Pereira, Mike Machado, Zarine Daruwala, Hari Prasad, and many more.

And your favorite composers?

Roshan, Naushad, O P Nayyar, Madan Mohan. But, only one person stood out R.D. Burman! What a variety he gave. If I had an R.D. Burman recording the following morning, my sleep would be disturbed, thinking about what he would make me do the next morning (especially during my early days). It was highly creative work, but very challenging and unpredictable.

Did he allow you musicians to experiment?

Very much! It was a very non-conventional approach. Suppose I was playing the drums, he would ask me to play the same on the side, on the ring-just about anywhere. Change of surface, change of sticks, and change of style—everything goes in his quest for innovation. For Jeevan ke har mod pe, he made me play the Xylophone holding the sticks the wrong way; that’s the creative genius he was.

Being a highly sought-after musician, you were being called regularly for recordings. Why did you quit?

I wanted to move out of Mumbai as I was sick of the noise and pollution. I wanted to lead a quieter life, developing farmlands, properties, etc., like Gary Cooper. Importantly, I was deeply affected by Sunil Gavaskar’s statement when he was asked about the reason for his early retirement. Gavaskar stated Vijay Merchant’s words that in sports and creative fields, one must retire being asked, ‘Why are you retiring?’ rather than ‘When are you retiring?’

Was excessive dependence on technology one of the reasons for your departure in the late eighties?

Basically, I am an acoustic musician, and I loved and experimented with acoustic sounds. From the shape of things that were coming, I did not know whether to appreciate musical or technical talent. I felt that as acoustic musicians, we had spent years of practice getting the particular speed or grace required for a song, and now, with the flick of a knob, the speed of the recorded piece could be altered substantially. It was extremely demoralizing.

When you played and recorded a great song, did you ever feel that it would become a hit?

We did our job to the satisfaction of the music director; other than that, we didn’t dwell on things too much. When I played that extra-long pick-up on the drums for the song Piya tu ab to aaja, all of us used to laugh and make fun of it, but soon it became a super hit.

You, and in particular, the Lord family, were called upon whenever good Ghunghroo playing was required. Songs like Nadi naare na jao, Dil cheez kya hai, Piya baawri, etc., resonance with your artwork. I understand that you played Ghunghroo patterns for which notations, like in the case of Tabla, were written. Vyjayantimala’s dance ballet Chandalika was one such composition. Please explain.

This was an hour-and-a-half-long ballet having intricate Ghunghroo from the beginning to the end. She probably liked my work on the song recordings and asked me to play. Choreographers like Gopikrishna, Hiralal, Sohanlal, Saroj Khan, etc., insisted on calling our family for their dance numbers. They showed us the action and we wrote the Ghunghroo patterns accordingly to go with the song in a synchronized way. Otherwise, Ghunghroo is mostly played beat to beat, which may clash with the dance movements.

Do you remember any unusual incidents?

Once in the West Indies, after my performance, the audience physically checked me to see whether I used my arms or some electrical contraptions to play the Drums since my hands were moving that fast. This was a big concert and my playing was reported in headlines “as Gene Krupa of India” in the newspapers there.

It was immense fun playing live on stage with Kishoreda. He was a riot on stage with all his comic improvisations. He did no rehearsals with us, so we were happy. (Other singers used to rehearse for six months before stage shows.) Even if he made a mistake, he would cover it up with his antics as if it was meant to be. But he used to plead severe nervousness before appearing on stage. But once on stage, he would somersault and do whatnot!

Memorable songs in which Burjor Lord (Buji) played:

Drums

Raat akeli hai – Jewel Thief ’67 | Gulabi aankhen – The Train ’70 | Phoolon ke rang se – Prem Pujari ’70 | Dum maaro dum – Hare Rama Hare Krishna ’71 | Piya tu ab to aaja – Carvan ’71 | Aao na gale lagao na – Mere Jeevan Saathi ’72 | Duniya mein logon ko – Apna Desh ’72 | Jaane jaan dhoondhta – Jawani Deewani ’72 | Lekar hum deewana dil – Yadon Ki Baarat ’73 | Mehbooba mehbooba – Sholey ’75 | Chand mera dil – Hum Kisi Se Kam Nahin ’77 | Yeh mera dil – Don ’78

Brushes:

Main hoon jhum jhum – Jhumroo ’61 | Beqaraar karke humen – Bees Saal Baad ’62

Chinese Temple Blocks:

Ab kya misaal doon – Aarti ’62 | Kora kaagaz tha yeh man – Aaradhana ’69

Conga:

Guzar jaaye din – Annadata ’72 | Sun sahiba sun – Ram Teri Ganga Maili ’85

Bongo

Chhodo kal ki – Hum Hindustani ’60 | Kaanton se khinch ke – Guide ’65

Percussions:

Ek haseen sham ko – Dulhan Ek Raat Ki ’66 – Madan Mohan | Ai mere vatan ke logon ’62

Ghunghroo:

Mose chhal kiye jaaye – Guide ’65 | Kajra muhobbat wala – Kismat ’68 | Dil cheez kya hai – Umrao Jaan ’81

Glockenspiel:

O sajnaa barkhaa – Parakh ’60 | Jo waada kiya wo – Taj Mahal ’63 | Rahen na rahen hum – Mamta ’66

Vibraphone:

Koi humdum na rahaa – Jhumroo ’61 | Chhupalo yun dil mein – Mamta ’66 | Kuchh dil ne kahaa – Anupama ’66 | Aa jaane jaa – Inteqam ’69 | Mere sapnon ki raani – Aaradhna ’69 | Tum pukaar lo – Khamoshi ’69 | Jaane kahaan gaye – Mera Naam Jokar ’70 | O meri sharmilee – Sharmilee ’71 | Chhoo kar mere man ko – Yaarana ’81

Xylophone:

Ek tha gul aur – Jab Jab Phool Khile ’65 | Piya tose naina laage re – Guide ’65 | Chal chal chal mere – Haathi Mere Saathi ’71 | Saamne yeh kaun aaya – Jawani Diwani ’72 | Jeevan ke har mod pe – Jhootha Kahin Ka ’79.

Comments (2)

Superb

Beautiful! Another lovely song that he played the vibraphone for is Mujhe Jaan Naa Kaho Meri Jaan (Anubhav)