God’s Own Musician – Ranjit Gazmer (Kancha)

- M..It ro It was located on the ‘Jal Pahar’ hill.It was located on the ‘Jal Pahar’ hill.Shankar Iyer | burmanfan@yahoo.com

Over the years, Indian music has been broadly identified in two forms. Classical music, associated with a certain grammar and structure, was considered the music of the masters. Born in the kings’ palaces, it required basic dedication and constant practice to learn this form of music. Moving down the generations, the effort needed, and the binding tenets were perhaps the reasons for it to be practiced and embraced by only a certain class of the Indian population.

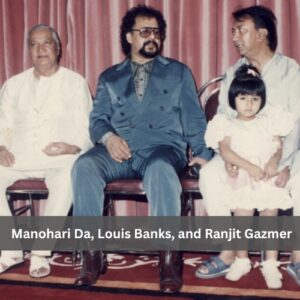

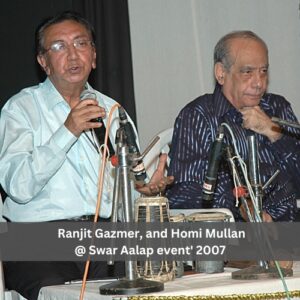

It was an enlightening moment when Ranjit Gazmer stepped on stage in the year 2007 at the Swar Aalap event and shared some insights into his most cherished career as a musician. He was felicitated by Swar Aalap at the same event.

On the other hand, there has been another form of music – folk music. Said to have been born out of the local soil, every common man on the street could hum the same. Be it the lush green farms or the flowing rivers, a farmer’s tune would be to make his work easier, a laborer to forget his physical and mental stress…Needless to say, such music gained popularity and easy acceptance mainly because of its simplicity and ethnic appeal.

Hindi film music too, to a large extent, has relied heavily on folk music to express itself. India’s social and geographical diversity have meant different kinds of approaches to music, and different styles of folk music. Add to it, the region’s distinctive folk instruments and you have musical expressions that represent their unique folklore. Music composers and musicians from different parts of the country have brought with them this folklore that has not only given a special touch to film songs but also painted a picture to depict the mood of the surroundings they have been pictured in.

Hindi film music too, to a large extent, has relied heavily on folk music to express itself. India’s social and geographical diversity have meant different kinds of approaches to music, and different styles of folk music. Add to it, the region’s distinctive folk instruments and you have musical expressions that represent their unique folklore. Music composers and musicians from different parts of the country have brought with them this folklore that has not only given a special touch to film songs but also painted a picture to depict the mood of the surroundings they have been pictured in.

One such god’s own musician who brought northeast folk music to Hindi films is Ranjit Gazmer. Fondly called Kancha, Ranjit Gazmer brought with him the ‘Maadal’ an instrument that produced the drum and rhythm effect so synonymous with the mountainous landscapes, hilly terrains, and serpentine ghats of regions like Darjeeling and Sikkim. The origins of the Maadal can also be traced back to Nepal and its use in local folk music. Used as a percussion and rhythm instrument in many Hindi film songs, the rich sound of the ‘Maadal’ has given a special sheen and luster to the music of the 1970s and the 1980s.

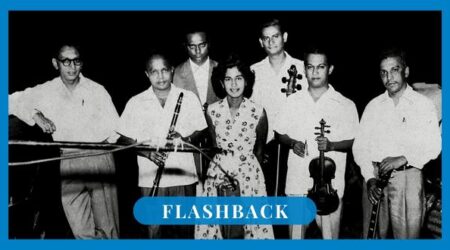

Born on 3rd October 1941, Ranjit Gazmer’s early days were spent in the musical backdrop of Darjeeling. Belonging to a family of gold merchants, young Ranjit let the mystique of the hills hone his musical skills. During those formative years, he played with renowned musician Louis Banks and his illustrious father Georgie Banks. Having learned to play almost percussion instruments like the Drums, Tabla, Dholak, Harmonium, Vibraphone, Xylophone, Organ, and Maadal, Ranjit Gazmer spent his next few years playing for Nepal Radio before the attraction of Hindi films brought him to Bombay in the early part of the 1970s.

As a Maadal player, Ranjit Gazmer was a key member of the trend-setting musical team of composers R D Burman and S D Burman during the 70s. His Maadal playing with its unique laykari and tonality has also lent a special tang to the compositions of Ravindra Jain, Bappi Lahiri, and Ram Laxman.

I met Ranjit Gazmer (Kanchaji) at his residence to discover more about the man and his music…

Tell us something about your childhood. When did you start learning music?

I was born in 1941 in Darjeeling. Generations of ours have been in the gold business. During the British Raj, our family (Gazmers) traded gold and silver in the entire district of Darjeeling and Sikkim.

My musical inclination started when I must have been around 13 years old. My brother-in-law, Hira Kumar Singh, was a well-known Tabla player in Darjeeling. I used to watch him play regularly and was slowly getting attracted to the instrument. Seeing my interest, he began to encourage me and introduced me to a friend of his, Mr. Wangel. He was kind enough to train me on the instrument. I also learned Indian classical music from vocalist Ustad Hare Krishna Sahi by accompanying him on the Tabla for many concerts.

Was Tabla the only instrument you learned?

No, also the Harmonium and Drums. I must tell you about this incident. This must have been the late 1950s or so. Georgie Banks (father of well-known musician Louis Banks) had an English music band that played in Darjeeling. Georgie Banks himself played the Piano and Trumpet; Louis Banks played the Guitar. Their drummer was not available for one of the band shows. I got a great opportunity of doing that job. Learning to play the drums from Louis Banks, I practiced for 7 days and performed at the show!

Did you get to do a lot of many shows immediately after that?

Not really. As a student at the Turnbull High academy, I learned music from Shri Amber Gurung, a noted music director, musician, and singer. Amberji also gave me opportunities as a Tabla player during rehearsals, public performances, and a few recordings. This helped me to learn more and more classical rhythms, besides the catchy pick-ups and beats that helped me later when I started to record for films.

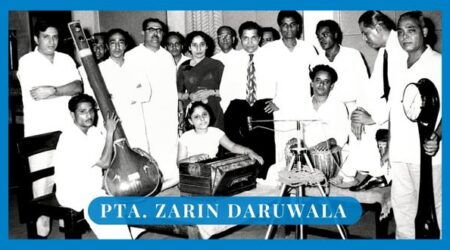

After we departed from the academy, I teamed up with my friend Sharan Pradhan to form a music group. We launched ‘Sangam’ along with our other musician friends Aruna Lama and Jitendra Bardewa. ‘Sangam’ ran under the banner of ‘Sharan-Ranjit’. I played the Tabla while Sharan played the Mandolin. The group also had my good friend Peter Karthak. Sharan and I recorded our first 78 rpm disc record then. This was in the year 1962. The stint also helped me learn music arrangement besides also learning to assist Sharan with his melodious tunes.

What happened next?

Marriage (laughs). In 1964, I married my wife Kusum and began working at the IGRD (Indian Gorkha Recruitment Depot) to support my family. It was located on the ‘Jal Pahar’ hill. The assignment was to teach raw Nepali army recruits the English alphabet and a bit of a map reading!

On the musical front, all musicians of Sangam club had got dispersed. Peter and I were left with managing the ‘show’ with Peter penning words to my tunes and acting as the occasional guitarist. We, however, occasionally played together with Louis Bank’s music quartet at the Darjeeling Gymkhana.

Are there any specific achievements of those years that you would like to share?

Peter and I formed a group called ‘Hillians’ which was the first indigenous Rock-n-Roll band in Darjeeling. This was because Georgie Banks left his band and went to Nepal. The stint helped me learn more percussion music as I played more and more on the drums.

We also began to develop a liking for music chords. I remember we had created a unique chord pattern for one of our compositions called ‘Mayalu’. Louis Banks assisted us and a refined interlude with the help of Peter’s improvisation ensured that the song was a super-duper hit in Darjeeling. In fact, Peter even wrote the words and sang the song which was recorded by the ‘Hillians’ at 78 rpm at Hindustan Records in Calcutta in 1965.

As a musician, when did your association with Nepal begin?

During 1966-67, Nepal Radio started. We were keen to play there because it would have given us some money. Peter got an opportunity with the Guitar and me with the Tabla. We were fortunate to assist the then Nepali music maestros like Gopal Yonzon, Narayan Gopal, Nati Kazi, and Shiva Shanker. Most of the major recordings on Nepal Radio had both of us playing as musicians.

Another great turn of fate occurred when I visited the Royal Nepal Academy (RNA). I bumped into Mr. Ram Saran Darnall who used to know me since my Darjeeling days. He was keen that I join RNA as a musician. I did so, enjoying my stint playing the Tabla, Chords, and some of the other Percussion instruments. During those days I also met an old Darjeeling friend who worked as the Manager at Nepal’s Hotel Park. He encouraged us (Peter and me) to form a music duo band. We agreed and landed an evening job at the hotel.

Nepal really kept me busy musician with the RNA till 2 pm, recording sessions with Nepal Radio after that and the evening band show at Hotel Park. In connection to Nepal, Ranjitji mentioned at the Swar Aalap event that the instrument Madaal became his identity due to the Nepal music touch. He used his folk skills for mainline Bollywood music.

How did your entry to film music happen?

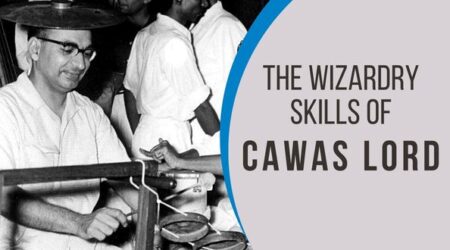

That’s another story. One day I met well-known instrumentalist and musician Manohari Singh at the RNA. He had come to Nepal with his family for a holiday. He had known me and my family since the early Darjeeling days.

It was surprising for him to see me at the RNA and enquired how I reached there.

I narrated my story and hesitantly asked “Can I get a chance to play in Bombay”? Manoharida encouraged and said, “Come and try. Make your own accommodation. I will introduce you to people in the industry”. “Kisika ho jaata hai, kisika nahin”, he philosophized.

In connection to Nepal Ranjitji mentioned at Swar Aalap event that instrument Madaal became his identity due to the Nepal music touch. He used his folk skills for mainline bollywood music.

So, what did you do?

Three months later, egged on by my wife, we finally arrived in Bombay. This was in the year 1970. In fact, it was December 25th. My brother-in-law had already moved to Bombay and we went to his place. I visited Manoharida’s house the very following day, where I also met his brother, Santosh. Manoharida welcomed me warmly and finally said “Kal aa jaana”. He gave me Sachinda’s (SD Burman) address.

When I reached Sachinda’s place, he asked “Koi gaana aata hai”? I replied “Yes”. I then met Panchamda, who asked me to attend his recording the next day. Santosh ji asked me if I had brought the Maadal with me. Though I had never played the instrument, he asked to carry it with me.

What happened the next day?

With the Maadal wrapped in a newspaper, I reached the recording room. I immediately recognized Homi Mulla, who I had earlier met in Calcutta. As I walked in, I saw Dev Anand Saab with Panchamda and his other musicians. Dev Saab was making ‘Hare Rama Hare Krishna’ then and the story was based in Nepal. He looked at the Maadal in my hand and immediately remembered having seen it in Nepal. He wanted the same ‘Nepali’ touch for his film’s music and I was requested to play a tune. I played the Nepali song “Kancha re, kancha re”. They liked it very much and recorded the same tune with Hindi words. “O re ghunghroo ka bole” from the same movie was the first ever Hindi film song that had the sounds of the Maadal which I played! That was also how the name ‘Kancha’ stayed with me, ever since!!!

Can you tell us something about the Maadal and what makes it special?

Can you tell us something about the Maadal and what makes it special?

The Maadal is a popular folk musical instrument from Nepal. Nepal widely uses this drum. Leather is used to make it. It has a wooden body, and looks like a tiny Dholak. Most Nepali folk songs are accompanied by the playing of this drum. For Nepalis, folk music and dancing has been the main form of entertainment available. On holidays and festival days, the men of a village or neighborhood typically gather in a circle for an evening session of singing and socializing. The musical backing always consists of the Maadal (played by holding it horizontally)

Northeastern provincial states of Darjeeling and Sikkim also use Maadal as a rhythm instrument. The original regional Maadals from those states (known as ‘Purbevli Maadal’) were slightly bigger in size than the Paschimi Maadal that I used for Hindi film songs. This was because those Maadals could not give the desired sound output in the recording studio. However, I did use the Purbevli Maadal in my highly successful Nepali film ‘Darpan Chhaya’ (Yr, 2000). Subsequent to the movie’s success, I have used it in my recent movie scores.

How did R D Burman use the Maadal in his songs? There has been a very predominant use of the instrument in his music…

The unique tone of the Maadal fascinated Panchamda. He not only used it in many songs for its main rhythm but also used it extensively as a side rhythm instrument. Using it mostly in ‘off counts’ between the main rhythm counts, he packed in a different punch that helped enhance the main rhythm too. According to music’s requirements, he ensured I tuned the Maadal correctly.

Panchamda was so fond of the instrument that he wanted to use it for every second song. You may have heard the story of the making of the famous song “Lekar hum deewana dil” from the Nasir Hussain movie ‘Yaadon Ki Baarat 73. The song was first entirely recorded without the Maadal. Panchamda suddenly realized that there was something amiss in the song. He remarked, “Is mein toh mera signature nahin hai”. That was truly a big compliment to me!! He recorded the entire song again with the distinctive Maadal pieces at the end of the interlude music kick-starting the Antara!!!

The use of Maadal Tarang in “Tere bina jiya jaaye na” is an example of Panchamda’s will to try out new things. For one song, he used both the Purbevli (big-sized) and the Paschim (small-sized) Maadal to create a special effect…Needless to say, the song required that type of feel…It was “Dil mein jo baatein hain” (Joshila, 73)

Have you played the Maadal for any other music composers?

Yes. After the first use of Maadal in ‘Hare Rama Hare Krishna’, all music composers wanted to have its sound in their music. I have played for Dada (SD) Burman, Bappi Lahiri, Ravindra Jain, and Raam Laxman. Ravindra Jain used it to a great extent giving the rural feel and flavor to his songs.

Have you composed music for any films?

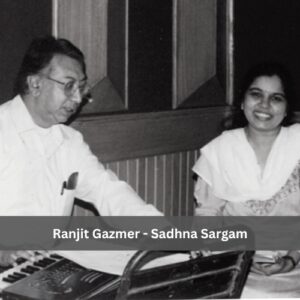

I have given music for Nepali films like ‘Darpan Chhaya‘, ‘Saino‘ ‘Samajhana‘ and ‘Kusumey Rumal‘. I was fortunate to get noted playback singer Asha Bhosle to sing her first Nepali song in ‘Basuri’, (1982) which I scored the music. The movie, directed by Tulsi Ghimiray, also marked the debut in Nepali film music for today’s popular playback singer Udit Narayan. In Hindi films, I have worked as Chief music associate in R D Burman’s last movie “1942- A Love Story”. I also gave the title and background music for the famous TV serial ‘Ajnabi‘

Who are your favorite music directors?

RD Burman, Madan Mohan, Shankar-Jaikishan, Salil Chowdhury, Roshan, and SD Burman. Madan Mohan Sahab and Roshanji were melodious composers. Dada Burman excelled in folk music. I admire and respect all these music directors. They all had their own individualistic style and gave some very great music.

What are the memories and incidents that have stayed with you in your long career?

I clearly remember the incident when the song “Hum dono do premi” (Ajnabee, 74) had been released and had become a rage. Lata Jee liked my solo Maadal piece (played throughout in the background). As she was passing beside me after a song recording, she looked at me and said “Kancha, bahut achha”!!!

Another thing that has stayed with me has been Manoharida’s support and love. He is one of the very few in the industry who calls me Ranjit and his affection has been extraordinary. In fact, though he has five brothers, he always identified me as one of them.

Leave a Reply